Family Dyes

Tami Katz-Freiman

“Wanted for a video art project: individuals, couples or families for a documented meal.” This was the wording of Meirav Heiman’s ad published in the paper and on the Internet toward the current show. After a long series of interviews and meetings, the final participants were selected, among them actual relatives of the artist, and were cast in various combinations to form six fictive families. These ranged from the traditional nuclear family of a father, mother and two children, through an alternative family of two grandmothers and two grandchildren, to a family of two mothers, an aunt and three children.

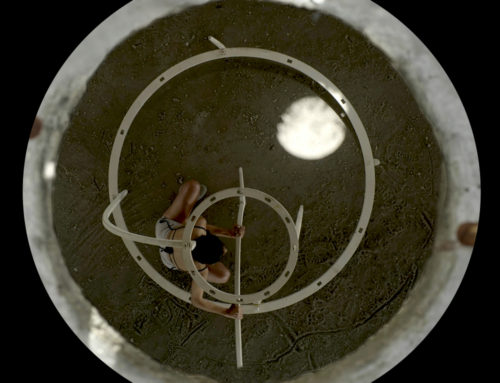

For each of these invented families the artist matched a residence in the suburbs; she modeled the dining and living rooms in keeping with their staged image, and invited the participants for a meal she cooked by herself. Her instructions toward the meal shoot were minimal yet strict: the participants were asked to come dressed in a certain color, to eat naturally and finish the meal within exactly twenty minutes without talking to each other. Each of the meals was documented in a single shot with a static camera, without rehearsals. Through editing manipulation, Heiman played the meals in reverse, so that they are in fact seen from end to beginning at an accelerated synchronized speed.

The show is made of five monitors, simultaneously and incessantly screening five meals in five colors: yellow, orange, red, black, and white. All the meals begin and end at the same time, and are screened in a loop. The sixth meal, likewise familial, is projected on a separate wall, only this time the diners – father, mother and three children – are seen pulling out bags of snacks and cans of drink, eating them while jogging in the open landscape.

The white meal is held in an antique-style living room. The dining ‘family’ includes two grandmothers and two grandchildren, a boy and a girl, who eat cream cakes and drink milk. The red meal is an all-girl meal – two mothers, an aunt and three daughters. It is held in a living room against the backdrop of a collection of reproductions and tacky wall decorations. Some of the participants wear red wigs. They drink wine and eat salmon and spaghetti with ketchup. The yellow meal’s participants are a father, a mother, a son, and a daughter – a traditional nuclear family – all wearing blonde wigs, eating corn and drinking lemonade. Two sons and three mothers eat the most aristocratic, black meal in a fancy dining room (one of the mothers dines wearing gloves). They eat chocolate fondue and drink coke. And in the orange meal (a candle-lit breakfast), a redheaded family – father, mother and three daughters – eats in a standard dining room. The menu consists of pancakes and orange juice.

This is not the first time Meirav Heiman cooked meals for strangers, creating human situations of anonymous intimacy. In the project Sister of Mercy, at Borochov Gallery, Tel Aviv (January 2001), she documented blind-date stories with people she met in chat rooms on the Internet, and invited for a meal at home or in places where they felt comfortable. There too, Heiman dictated the date conditions: you will receive a meal and intimacy and in return, expose your identity and be documented with me. The results attested to the bizarre nature of the encounters: with one of them she was photographed in bed, with another – during a romantic candle-lit dinner, and with the third – in the bath tub.

“I was fascinated by the anonymous intimacy of the media,” Heiman said at the time. The desire to shatter the mask of anonymity made possible by virtual space involved risks, which, in turn, generated the tension she is after – total control of a clearly uncontrollable situation. In an interview published in proximity to the project’s presentation, she confessed: “ I was willing to do anything, I talked to everyone, boys and girls, perverts, lonely-hearts, liars; witty and smart, bitter and naive, professors and fakers.” The current project is a direct sequel to Sister of Mercy, only here the idea was expanded – from the intimacy of a couple to familial intimacies. This time Heiman took fewer risks and made sure she has more control. The random and unexpected were filtered through the preliminary interviews and meetings, thus allowing for exact casting of the fictive familial combinations.

In Gullet too, she focuses on the gap between the ideal and the concrete, the virtual and the real, the personal and the anonymous. The individual virtual identity of the chat rooms, however, is replaced by the fictive family she has fabricated, a family that is, in fact, a mixture of acquaintances, authentic family members, and total strangers. The radical treatment, the props, the stylized design, the humor, the exaggeration, and the grotesque lend each of the meals an air of familiarity and estrangement at the same time. On the one hand, there is the mundane banal ritual of a family meal; on the other – the setting looks like a maquette, like theatrical decor. The houses ostensibly represent the stylistic spectrum of the kitsch-oriented Israeli bourgeoisie (plastic flowers and animal figurines on the windowsill). The ritual becomes mechanical; family members resemble a monstrous shredder (note how they nibble on the corn and saw the pancakes). The reverse screening creates a discharge effect, as if the food is returned from the mouth to the plates that gradually pile in the course of the meal. The body language is distorted, and the reverse sound transforms the rustle of knives and forks into a hiccup-filled fencing match.

Heiman subverts the fantasy of the family’s sanctity. A potentially intimate graceful moment of familial togetherness becomes a hollow choreography that speaks of loneliness and detachment. The meal remains functional (“In the museum they will eat continuously for eight hours a day”). Apart from passing the salt and pepper, there is no communication whatsoever between family members. Each keeps to his/her own plate. Every bite they take into their mouths gnaws upon the utopian harmony of the family unit; the idyll is violated, and as the minutes pass, the meal is increasingly perceived as an empty ritual of collective stuffing.

The ‘family institution’ is defined in terms of relations based on birth or marriage, namely on shared origin. A more open definition would describe a ‘family’ as a hierarchical organization or as a group of people who identify themselves as related to one another and maintain intimate relations of inter-dependence. In any event, the meaning of the term is socially structured in culture. Heiman’s definition of family is determined by color, not by blood relation, nor by biology. The intra-familial relations were determined arbitrarily through color unification: the family of yellows, reds, blacks, oranges, whites. A twofold goal was thus obtained: suggesting a class-oriented social critique while subverting the standard family and challenging divergence within the family.

The personal identity of each member of the fictive family has been assimilated and absorbed within the ‘organization.’ All of them are, in fact, puppets in a set. The figures appear stereotypical and hollow, and the relationships silenced by order are disturbing in their alienated and superficial nature. With typical humor, Heiman places an unflattering mirror, reflecting the eating customs of the average Israeli family. Unlike American contexts where the familial gathering is regarded as artificial to begin with, in the Israeli Middle-Eastern context a family meal is considered warm, at times emotionally stormy. In this respect, the very act of silencing the Israeli by the dining table is tenfold radical. From a sociological-anthropological point of view, Heiman ridicules the food-oriented culture, highlighting the boredom inherent in the eating rituals and hinting at different types of anomalies within the family: eating disorders, abuse, incest. As in the work of American artist Robert Melee whose works are exhibited alongside Heiman’s, here too a hidden violence, pain, and a great deal of sadness are revealed under the veil of grotesque fantasy.

Gullet is deeply-rooted in the contemporary post-feminist discourse. Many female artists have addressed the food obsession in an attempt to undermine conventions pertaining to the traditional functions of the woman as food-provider. In this context, one can mention Cindy Sherman’s series of film stills from the late 1970s where she plays the role of a housewife in the kitchen, as in Holliwoodean clichés, or her 1987 series of color photographs depicting the remains of festive meals, highlighting the repulsive aspect of eating rituals.

The link between consumerist culture and the kitchen and the affinity between body and food (in the context of interior and exterior) have led many women artists to deal with the food obsession typical of affluent society as part of the discourse of the ‘abject’ – the rejected and despicable, disgusting and sickly. Thus, for instance, Sophie Calle has composed a color-coded diet for each day of the week (The Chromatic Diet, 1998); Janine Antoni nibbled and gnawed for weeks on two large lumps of forbidden carbohydrates – lard and chocolate (Gnaw, 1992); and Marina Abramovic starved herself for twelve days spent at Sean Kelly Gallery, New York (2003).

Under the guise of a comic fantasy, Meirav Heiman too offers a poignant comment on the eating culture and family entity. Her nice families spit their food into the plate, and all the acts of biting, munching, scrunching, chewing, and swallowing appear non-gratifying and automated. The family meal has been neutralized of any feelings. All that remains are the food-related gestures. This is achieved through a strategy of estrangement (note the title of the piece, Gullet). In keeping with the medieval traditions of the grotesque and carnivalesque, everything is exaggerated but not all the way. Like the decision regarding the food colors and their matching to the colors of wigs and outfits, so the dosages and ratio between humor and subversive energy, between normal and abnormal, between familiar and ridiculed are carefully calculated. Next time we sit at the table, we won’t be able to avoid thinking about this bizarre game called ‘family meal.’